|

by Kaitlyn Crow.

So, my immediate, first reaction after reading this piece? Wow. “What Kind of Vampire Are You?” pulls the reader through a transformation so many of us know: the turn, from an Aeropostale-clad child to something darker, salacious, coaxed too young by an older man with wicked intentions. I felt the fire, the Chatroulette eyeballs. Crosbie’s use of call-and-response—“Who were you in a past life?”—brings the reader through this transformation so effectively I found myself asking, “How was I turned?” This effect is underscored by the title—Crosbie asks and answers within their piece, but also asks the reader to wonder for themselves. The use of vampirism here is equally effective in threading the mood of this piece through each line. Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor played in the back of my mind while I read from call to response. Images such as “moon-laden skin / crawling with apparitions” and “your skin crawled to jaundice and gothic” amplified this mood, and I absolutely shuddered at “The way you softened / in his husky hands.” Crosbie’s piece will find itself seared in your brain, but it will not be “grainy and gray like a graveyard when it rained,” no —instead, this piece will stay with you with the same immediacy as the raised hairs on your arms, the softness of your skin, or the horror of knowing of men who understand “too young” and just don’t care.

0 Comments

Anita Cantillo reads an excerpt from "Origin Song", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue6/28/2021 by Jonathan Louis Duckworth. Doughty’s work of flash prose starts from a deceptively simple premise: the short questionnaires that in the Age of COVID have become ubiquitous features of health clinics and hospitals. However, beyond the opening question, which plays the concept straight, the piece wildly diverts from its quotidian premise. It should be noted, though, that while the end result of "Screening Questionnaire" is a surreal journey through the narrator/speaker’s headspace, the escalation that takes the reader from the tedium of screening questions to something entirely else is remarkably logical, in that each associative leap the piece makes is proportional and has clear linkages. Throughout the piece, Doughty relishes the opportunities to laugh with and at language and its inherent absurdity. Doughty illuminates how so much of human language is reliant on dead metaphors whose literal meanings must be ignored, even outright buried, lest they disrupt the tenuous realities we attempt to forge with our words. Lines such as “Alternatively, crow’s feet that then grew bodies and took flight” demonstrate this. Doughty also has fun at the expense of the piece’s unnamed protagonist, whose journey from hypothetical existence (the “you” referred to in the questionnaire) to a very real existence is established through increasingly specific details, such as a beautiful description of a bathroom tap overgrown with lichens. What is most effective about "Screening Questionnaire" is that despite the occasion and inspiration that created it, it feels more timeless than timely, not dependent on the reader being inside of the pandemic history bubble for it to have meaning and a capacity for exerting delight. This is down to the piece breaking away so entirely from its premise and becoming, as I mentioned before, something else. To paraphrase the piece’s closing question, “Isn’t that better than the alternative? by Ọbáfẹ́mi Thanni. The declaration of God to the persona to fold which begins the poem "The Temple Yields Like A Lamb", is a voice and allusion that continues and grows through the poem. The writer's response to the instruction that begins the poem is that of humour. As the poem progresses, this humour grows into a need for survival which takes the form of a lily; a marked presence to make the absence of the persona noticed, a mark to let the viewer or reader, know where to look. This growth continues throughout the poem, marked by a tension that is heightened with form. In the prosaic rendering of the poem, the line breaks often by the sheer weight of a declaration, only for the line to be sustained by the consequence or the subversion of the instruction. These subversions cause the words to be charged, to be both essential to and complicit in the resistance of the persona, such as in subverting the instruction to be good the resistance grows from description to action and the persona becomes worsted. The writer's voice redefines the expectations of yielding, of obedience, and lends agency to the very act of folding, of slivering by ensuring such acts are carried out by the subject itself. This agency is informed by mortality, by the possibility of pleasure, by a final word that replaces disappearance with blossom; that replaces dust with fruit. Becki Hawkes reads an excerpt from "Apple Lover", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue6/24/2021 TEXT: My favourite kind of apple? I place my palm against your hair, press until both of us are anointed with apple, crushed close, held by the scent of the green apple shampoo you started using after I told you how the right apple can throw you off completely, burst new buds in your mouth, make you bleed, sweat, pray for each torn crisp hit of sugar, squeezed out by your very own teeth. I love the hand-sized promise of them. I love Braeburn, Jazz, Granny Smith. I once saw five Red Admirals, wings vivid as hearts drink from the same fallen Bramley, saw their long tongues, dreamed I could feast too by Kris Hiles.

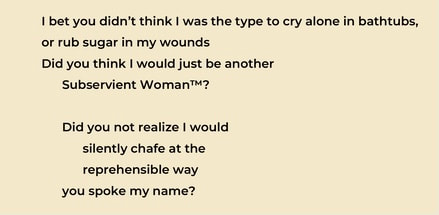

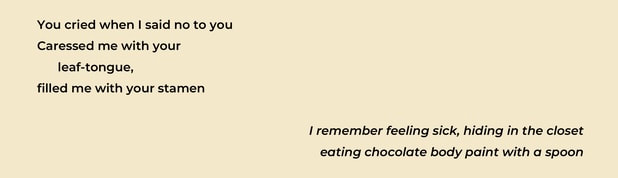

CW: sexual assault On the surface, "plantlove" is deceptively simple. Reading through, one can easily miss the subtle layers built into the words. This a poem that speaks of trauma in a language of trauma, layers that are not quite metaphor. The words wander over themselves in a swirl that will swallow you, and, taken to heart, make you lose your appetite. Alone, each section is powerful, but taken together, the nuance and complexity build. Flower images mix with food images, bitterness and violence mix with the confrontation of phrases like: I bet you didn’t think I was the type to cry alone in bathtubs, / or rub sugar in my wounds. The wrenching pain near the poem's conclusion also deserves to be acknowledged: I remember feeling sick, hiding in the closet / eating chocolate body paint with a spoon. by Rachael Crosbie. In "Sestina", the waltz of the stanzas lures you in similarly like The Haunting of Bly Manor—you’re in for a gothic piece dipped in romance. Also, there’s a lake involved. While violent, the poem is beautifully written, and its sestina form pushes the narrative forward better than any other poetic form. “Tonight my car’s headlights will beam the lake / cuing that waltz which lulls me back to Luke.” This immersive recount of a lost love pushes and pulls you throughout the poem, a natural ebb and flow, the dichotomy of life and death. Like the water in the lake, there is a certain stillness between the waves, a moment in the waltz, where that gap between life and death comes through. TEXT: When I first joined the queue, the hall bounced with hurried music. The tempo quickened my heart. I tossed my shoulders like I was renting the joints. In the queue, we had young punks wearing the velvet cordons like sashes, the even-younger-again punks looking for more cordons to copy them with, the shisha smokers who unfurled, built, and then unbuilt the bronze smokey goliath each time the queue progressed until they stopped queuing altogether and set up shop, we had the sand-shedding surfers inconvenienced to be out of their wetsuits and drysuits, like skin was a thin burden compared to wearable rubber, we had helpings of this and that, and it was all very funny and ironic, like we were all queuing with a collective sneer. I made a friend, my queue-neighbour––Laz––who had peculiar opinions on birdsongs. She said they were threats veiled in music. The punks liked that idea so much they serenaded the queue-skippers. We had drugs and the queue moved along okay during the highs. We were on the way to the thing. by Tahlia McKinnon. (photography by Hoss) With every wounding word poised to mark the skin, hit the throat, wind the lungs—like a bodily trauma, McCaela Prentice delivers blinding impact in just a few short phrases. There’s a delirium to the poem—a needing to make sense of things. A quiet unravelling. When we consider the titular word, Equinox, in this way, there’s an unpronounced prickle of melancholia, an undeniable ache of nostalgia – but not for what has come to pass in this protagonist’s life. For what was lost. For what was stolen. For what could and should have been. Shrouded in dark metaphors and allusions, the reader can only surmise, of course. But closing with a nod to winter—a season synonymous with death and decay, introversion and introspection—it’s as if the speaker is sharing a dark secret; making a confession; crying for help. A cry that can only echo through your bones, with each and every haunting line. Exquisite. by S. Preston Duncan. As cliche as the notion of channeling Shakespeare may be, I do believe in poetic channeling. I'm talking about writing you can feel, with distinctive contours. With ancient, living skin. Writing that leaves you silently self-narrating in its voice while you lean over the dishes hours after reading it. Writing that resonates in the primal drums that keep the rhythm of human history. "Speech from the Ur-Hamlet" by Lucy Frost is a spell cast in consonance and percussion, thick and dizzy as any southern summer. Astonished, almost, to be in its own presence. And this is what makes it relevant as more than an academic curiosity - its timelessly human character. Its capacity to merge with canon and still stand on its own. Its ability to take up residence within a reader, and assume a long forgotten throne in the back of their mind. Kat Ordiway reads an excerpt from "The High Priestess", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue6/15/2021

TEXT:

Then, I loved Miranda in the fierce, aching way a girl can only experience in high school and shortly thereafter. She was all that I had, and yet she had become foreign to me. We had been so quiet together as students, floating around the school in our matching plaid skirts and vests, never turning a head or catching an eye. We had each other and only each other, and when you are two, there is no need to be boisterous or to attract attention. But here she was, stopping in the middle of crossing a street to clutch her chest and inhale in wet, jagged gasps. Here she was, crying out while we walked in the park, making all of my former classmates turn their heads. Once, when we were sitting in my bedroom, she collapsed on my desk then slid to the floor, dragging all my textbooks with her. I was positive she’d stopped breathing, and in the second before I dialed 911 her eyes flew open and she screamed, “a noose in the night.†I didn’t know what to do with her. We were only children, there was no younger, pestering sibling in which I could confide; her mother, with her tattooed eyeliner and over-tweezed brows, had always made me nervous. When people approached Miranda, asking if she ever saw them in her visions, I wanted to shed her and to get away from home as soon as possible. But when she crawled into bed with me, her hot form against my back, I felt a thread attach us again and again.

by Ruairi White. Ashley Cline’s "mercy! mercy! (how we survived the winter)" is a poem about letting go. In three stanzas, Cline takes us through a break-up that’s as gentle as it is devastating, juxtaposing tenderness and violent imagery to mirror the emotions of a relationship at breaking point. Dying moths and swarming mosquitoes bring a sense of claustrophobia to a sunny afternoon outdoors that perfectly conveys the dread and heartbreak of having that conversation. The poem opens with two song lyrics which sum up the two parties in the relationship: the first is the chorus from Robyn’s "Call Your Girlfriend", a break-up song about doing the right thing by ending a relationship; the second is a shorter quote, from Cher’s "Bang Bang" - "My baby shot me down". The disconnect between these two lyrics—one communicating a bittersweet sense of duty, the other blunt heartbreak and betrayal—sets us up for the core conflict of the poem before it has even begun—"mercy! mercy!" isn’t just about the pain of not being ready to move on, it’s about the pain of knowing your partner already has. Cline refers to the break-up as a "mercy killing", and this notion of mercy as a well-meaning but destructive act is the foundation of the poem. To the speaker, mercy would be allowing them to love in peace; their partner’s good intentions mean little to them when they’re suffering such a heartbreaking and bitterly one-sided loss. This comes through in every little detail of Cline’s writing, from the description of the girlfriend as an "opponent" as she holds the speaker’s hands, to the comparison of her supposed mercy to moths burning in flames. The poem ends with a much shorter third stanza, which drives the emotion home in a blunt final line. When it comes to raw vulnerability, "mercy! mercy!" pulls no punches. by Ashley Cline. CW: postpartum depression What does it mean to be haunted; to be made to disappear—into a new life, a new home, a new anything at all, really—like magic? "And what you see here is an ordinary brown moving box. When you put all your clothes and dishes and photos and vases and toothbrushes and toys inside, poof!, nothing changes. Ah, but look again. Everything changes. You are no longer here. And you are no longer you.” In “A Nursery Tale,” Emily delaCruz considers the ways in which we find ourselves as ghosts, whether of ourselves, our own minds or, perhaps, something more sinister still: “…I felt fine. My brain cogs may have been slipping, but they slipped so gradually that I barely even noticed…the thing about slipping into postpartum depression is that it is very slow, very gentle.” Gripping, in both narrative and its lush, haunting imagery—from the towering pine trees our narrator hates and the stream that runs beneath them like “a black crack in the clean woods,” to the small gravestones covered in “a handful of snow, like wedding white roses”—“A Nursery Tale” doesn’t hide its teeth, but rather, delights in showing the reader its slow, deliberate smile. Sometimes the best ghost stories haven’t any ghosts at all. by Carson Sandell.

“menagerie II” by Arielle Tipa is a short, yet gutting piece. In the space of six lines, they paint a picture of a grim menagerie. The poem depicts screaming and dying animals kept in containment. At first glance, the piece is nothing more than that—however, reevaluating the lines, you may discover another layer. What if the animals were humans, and the menagerie us, being contained by our government and other oppressive systems? This is a mesmerizing piece for its careful use of language and commentary on current events. A poem so delicately crafted, it should be studied. “orchis italica” is another poem Arielle Tipa knocked out of the park. This piece captures a feeling we've all experienced at some point in our lives. The speaker wants to shrink into nothing, but still yearns to feel the lips of a lost lover one more time. This poem is clever with its title. Orchis Italica, or commonly known as the Naked Man flower, is supposed to produce virility in people, yet the speaker feels powerless. There are a lot of levels operating with this poem. And even without breaking all of it down, the emotions it elicits are always worth the read. In “silk moth”, the speaker anthropomorphizes themselves as a moth, a pest the receiver of the poem was warned about. The speaker says they have “tapped the lightbulbs without forgiveness” which suggests they are unapologetic for the fact they have seen a brighter future. To me, this poem encompasses a relationship gone sour, but the speaker knows that they are all the receiver of the poem has. Even saying, “eat me and there will be nothing left.” The speaker stays out of sympathy or some wicked reason, even though they’ve seen how amazing escaping the situation would be. This poem can be read as a lover staying with someone they fell out of love with, or it can be read as a lover, the receiver was warned about, finally coming to terms with who they dated. Either way, this poem is mind-blowing, beautiful, and leaves a lot of room for interpretation. by Elizabeth Joy Levinson. (art pictured by Sara Blaske) “The Bicycle Rack at the Beach” by Lynn Finger is a poem of unlikely juxtapositions that take the reader into an underwater dream built around deft language and stealthy turns. It begins simply enough, the human relic of a wayward bicycle rack that ends up underwater, the “ribs” of which become a home for seahorses. We know how a shipwreck can become an underwater city, but a bicycle rack is something far less tragic and for that, almost more compelling as a ship was never so mundane; the transformation of the bike rack that much more magical. And "the petal shavings from the moonlight" reveal more than they should; the narrator herself stitched to something as fluid, as elusive as the glassy ripples. This is the nature of all relationships, isn't it? As difficult for us to understand from within as they are to understand from those outside of the relationship. This is a poem I will return to again and again, as each reading reveals something new, a surprise of language or a surprise in the self. Aura Martin reads an excerpt from "The Quiet Dark", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue6/3/2021

TEXT:

I always had one kind of life in mind and things have turned out very differently. A story of a girl, or country, or a clean house where everyone knows her place. I buried myself all over the garden, but the pieces only sprouted into new riddles. I thought I was done stuffing fists in my mouth to mute the sound. by Emily delaCruz. Cantillo’s "Origin Song" sings the tenderness and fear of pregnancy. The pinto bean in her mother’s fleshy pit doesn’t see the world, instead she experiences it through the music of her mother’s life: green beans snapping, a broom grating, the soft cluck of hens. But when the poem turns on the soft thud of a rotten mango, hidden fears are revealed in a lawnmower choking and the syrupy singing of a drunk man. The triumph of this poem unfolds in its final lines where we meet the mother locked in prayer that transfers to her daughter. Cantillo’s subtle intertwining of hope and fear against the musical backdrop of life is masterful in "Origin Song". This is a poem that lulls then bites, leaving an echo. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed