|

by McCaela Prentice. I didn’t have any idea what soursop was before I read this poem—but how fitting. To compare a heart’s burst to a fruit just as overbearing. I read this just as the weather was warming up in New York, and it reminded me how spring can make love out of anything. And how that can make a fool out of anyone. We get those first cherry blossoms in April and everyone starts dreaming up new ways to be desired. All seasons are for longing, but spring is the best one. This piece shows so much need, and it does so much with so little space. It’s all unfurling. I think it really does capture the heat of a fling, or of something we get very dizzy hoping will become that. It wasn’t until the end that I felt this poem was less about the kiss and more about the pulling away from one. It feels to be about the vulnerability required in any offer of intimacy (and that bravery then feeling foolish). All that longing “For the doorbell, for the parcel, The kiss” is as memorable as it is tangible. ‘Marcel’ is “married with children”—is unable to fulfill the incessant longing that is so beautifully depicted in this piece. I had to read it a few times over to really understand the gravity of it. It breaks your heart so quietly.

0 Comments

S. Preston Duncan reads an excerpt from "Love[sic]", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue5/30/2021 by Tucker Lieberman. (art pictured by 婕 Venus Cohen) In the poem “Hollow Point,” Kris Hiles gently interrogates a transition through the sensory qualities of the moment. Though we are spared the details of whatever trauma has called for someone to “rearrange my skeleton,” the words nevertheless carry a raw emotional quality. We seem caught in a freeze-frame. “A splash in the tub” captures a brief occurrence, while “the flattening of a bullet, / just a little bit” suggests how a bullet may be deformed slightly by what it hits, likewise suggesting the instant of impact. Yet time does not move on. There is “the great slowing” and the observation that “the sapling is / the tallest tree,” perhaps meaning that there has not been, or will never be, enough time for the young trees to grow up. Life vanishes. We have “smoke,” “evaporation,” and “enough thirst to / drink the whole river”. We are left with “echoes”. With quiet mood and direct words, "Hollow Point" is a good example of how a poem can draw a reader into the poet's world to explore a sensitive and potentially scary subject. Insofar as this may be a meditation upon death, it could represent the closing, rather than the opening, of possibilities. But you may find something different in it. Each of us is, after all, “waiting for a tarot reading.” by Keshe Chow. This is a piece that creeps up on you. On its surface, it’s a sultry, seductive piece, with the seedy undertones of a cheap motel. It takes you on a journey; from the darkness of death in the first sentence through testaments to both religion and sex, Marlo Collins doesn’t lead you through this poem by the hand. She yanks you through the stanzas with the loosened belt of a bathrobe, strokes your hair, tells you everything will be okay, then stick a sly knife in your gut. The piece sways between pain and hope, hope and pain, then ends on pain. And toward the end, one gets the sense of someone who aches, who feels empty and rejected. Collins makes you feel like the protagonist, “with empty pockets and holes filled”. That is, until the last line, when the fourth wall is broken, and you can’t tell who is who anymore. Powerful stuff, and so deftly done. Lindz McLeod reads an excerpt from "Heavenly Bodies", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue5/26/2021

TEXT:

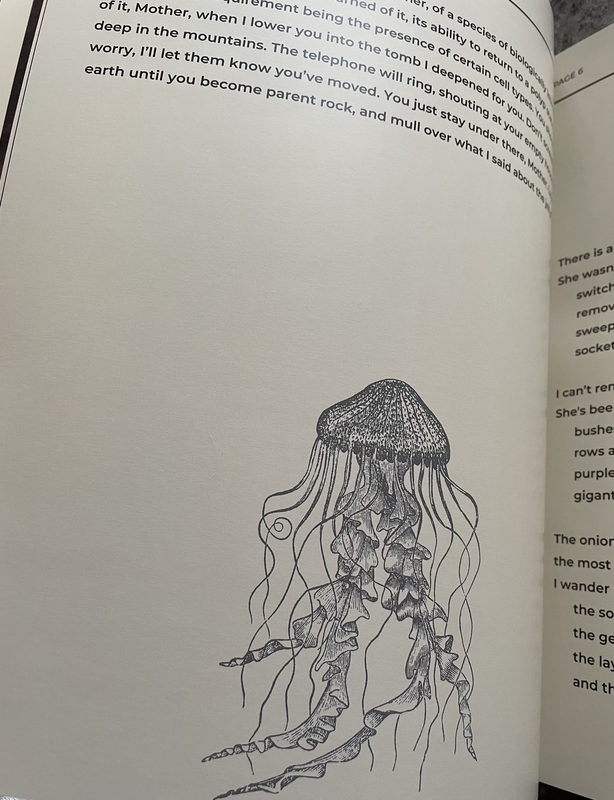

Even now, the palm of her left hand tingles in the presence of the celestial body, and a thick band of red, raised flesh on her thigh tells the tragic story of her first adventures in love. Flew too close, she thinks, too bloody close, and can feel her mouth water even in this arid, shimmering atmosphere. # ​ Joanna keeps the sun in the basement now, because it's too bright for the spare room. There's still daylight outside because it's a sun, not the sun; not her sun, but her sun—captured neat as you please when the little bastard came down to graze on the night meadows. They're slippery, not easily held in a net or cage; weaving like mercury to reform into human shape later. She'd had to buy special gloves too, a special rope, a heat-proof blanket to wrap it in. Black market stuff. by Dale Stromberg. (CW: death) Poets sometimes draw emotion from us by evoking sensations in the way of music or painting, with their words’ connexion to analytical sense left purposely tenuous. Likewise, the story underlying Shyla Jones’s “Jellyfish” is metaphorised into imagery and voice, and this narrative voice becomes its most lucid element. Who this narrator is, we cannot say; but, if we are who we are through other people, then she is who she is, at least within this piece, through her mother—the only other character identified, whom the narrator grimly apostrophises, and who allows the narrator no other physical or social contact. Within this enforced dyad seethes that original filial promise, and menace, to outlive the parent. The mood of the prose is of monstrosity, of animals born and slaughtered, of dampness and the tomb, as the narrator, in chilling assuredness, wends towards her mother’s end. How parent may have earned such animus of child is left to the reader’s intuition. The prose expresses the mother/child relation in terms of iteration: the mother’s birth, the deaths of the mother’s parents, and the mother’s own fate—to become, in the story’s final condemnation, “parent rock”, a buried substratum producing new soil. Iteration is also intrinsic to the piece’s central metaphor: a biologically immortal jellyfish that returns continually and perpetually to its polyp state. Child to mother to child again: there is a promise of cyclicality in this, though the narrator warns her mother, as this cyclicality looms, “don’t scream.” Earlier, we are told the mother, as a baby, “had hair like silkworm cocoons, stringy and pale”, and this hair, I speculate, was the tentacles of the mother when still a polyp, before she metamorphosed into an adult jellyfish—a medusa. by Lynn Finger. (CW: sexual scenario, religious trauma) In “Red Hairband,” Kaitlyn Crow takes us into the world of the senses that play out between two lovers inside their parked car. Crow is beautifully visual in the description of this intimate moment. For example, we are shown, “muscles wrapped around a lean backseat lover, torn dress, discarded seat belt buckle burning lines into spine.” Personal details are revealed by Crow, such as the red headband, church bulletin and condom wrappers, and we are immersed in the physical surroundings of the communion between these two. Crow shows us that sex and religious feeling have much in common: the awakening of the senses, the sense of surrender, the exploration of the other, and calling out the beloved’s name: “...they pledged their virginities and begged for Him to save their souls with hushed prayers and pursed lips, and she’s repeating that prayer now, lips miles apart…she screams save me save me save me.” The passion of the lovers erases the lines where the body ends, but also intensifies what the body knows. The plunge into this sensual catharsis is told in two sentences, as if Crow were showing the breathlessness of the lovers they portray. Crow illustrates that becoming lost in this union is a sacred moment, and both transcends and is created by the details of this communion—the red headband, the freckles, and sweat.

TEXT:

by Jared Povanda. (art pictured by Shawn Ferrari) (CW: death, grief) Cecilia Kennedy’s “Between the Scalloped Edges” is a story that revels in mystery. At first, the prose is intentionally vague and mired—as if plunging the reader into fog. In the first paragraph, the narrator says, “Something tells me to look up. I can’t quite place what that something is, but it’s one of those nagging feelings that grows into worry. Somehow, I’m forgetting something important. Sometimes, I think that if I reach up high enough, and in-between the curved edges, I’ll find a head or a face or something I’m not expecting.” Something, something, somehow, something, sometimes, something. The repetition is a purposeful device utilized to unsettle. To leave the reader off-kilter and unmoored. The main character doesn’t know what they’re looking for at the top of the kitchen cabinets or what they’re going to find, and the immediate tension for the reader is both wonderfully compelling and deliciously strange. As the piece moves, Kennedy weaves between the past and present to both paint a picture of minimum wage malaise and a deeper, shrouded grief. Something hidden. In a story full of stunning turns of phrase, my favorite detail has to be this one: “Sometimes, I make the mistake of throwing away an empty plate from a table, only to find out that the plate was not empty.” At some point, she remembers the food. She remembers the fullness of the plate, the exact opposite of emptiness, and that idea of memories almost sprouting like mushrooms continues on as the story unspools. Remembering—what the characters remember (a grandmother’s water pie, for example), don’t remember, don’t want to remember, find painful or impossible to remember—is this running theme throughout, and as the main character remembers her sister, the reader is again swamped in unsettling repetitious imagery. This time, Kennedy uses glass to unnerve the reader. To create an almost kaleidoscopic environment to keep the reader guessing about the truth of what happened to this family. As glass reflects and refracts the light, Kennedy expertly plays with the reader’s expectations of plot and language. What is, at least initially, a piece that is focused on a very human tension seems to veer into the spookily vague. The preternatural. “I find pieces in my hair,” the main character states, and then, “The manager at work has to pull me aside one day to talk to me about how guests have complained—how they’ve seen me picking pieces of glass from my scalp.” The past is merging with the present in unprecedented ways, or maybe what’s past has never finished haunting the main character. She says soon after, in a sort of dream or memory, “I work well into the night, gathering the pieces and finding where the edges meet…I look through them as if they were a complete window…I look through, and I’m seven and she’s five.” I almost want to ask whether or not the sister is a ghost—but I also know that’s how the family in the story has been treating this unnamed sister. Kennedy is exceedingly clever in how she doles out information, and in a bounding, reflective writing style—nearly ponging the reader back and forth—she has made me, in such a short space, want to theorize about What Really Happened Here. And is it better not to remember what actually happened? Is it better to forget? What about the glass? Is it some sort of haunted penance? There’s also the lovely detail about the main character working in hospitality when so much of what is described here is the opposite of hospitable. And I have to point out how the final lines linger and echo back through the story. How sleeping and waking are intertwined with the theme of remembering. How pain can paradoxically cause one to come to awareness (“I heard my name in hushed whispers—and something hurt—my hand, I think.”) while also causing a sort of emotional recession. A plunging once more into the fog (“They cared for me; they took me by the hand, but they never looked at me again. Looking is remembering.”). The final line especially speaks to the main character acknowledging the need for sleeping after a long day of playing. It is also true, though, that the sisters’ playing is interrupted by shards of glass coming away—falling away—as something sharp and awful will always come between them in both life and death, memory and dream, past and present. I so admire and respect what Cecilia Kennedy has accomplished here. “Between the Scalloped Edges” is a story of grief and murder, of multiple forms of loss, but it is also a story of sisterhood and what endures. There is pain and there is beauty, and it is the constant bouncing between these two poles that makes this story such a successful piece of art; readers won’t be able to help pondering over the fates of the characters long after they’ve finished reading. by Lucy Frost. (CW: discussion of sexual assault) In “Apple Lover” and “Some Boys Terrify Marine Creature (6),” two exuberant and elegant rhapsodies of survival, Becki Hawkes achieves a voice of lyric suppleness and epic durability, surveying the details of pain and the pitch of transcendence in a grand, fluid tonality whose precise modulation figures the shape and color and texture of experience. Her phrasing, sinewy with surprise and wit, laced with pressure points, shaped by the tensions of understanding gained in time, arrests the eye with sharp delineations and an awareness of meaning’s keen underlying edges—“some boys, / any boys,” the deceptively laconic parenthetical that haunts “Some Boys Terrify Marine Creature (6)” with its antagonist, is a vital moment to the art, scaffolding the eloquent balance of her perspective; definite but abstract, not an inch closer to or farther from us than it needs to be. The shading of generals and particulars, of “any” and “some,” signals the versatility of Hawkes’s poetic control. Likewise the shifting parameters of “Apple Lover,” whose festive botanical-entomological census—a whirl of lavish organic observation, crowned with “five Red Admirals, wings as vivid as hearts” amid feasts of “Braeburn, Jazz, / Granny Smith” (the omission of “and” before “Granny Smith” suggesting further bounties beyond the limits of enumeration)—spiral about the nervous understanding of trauma, the anxiety of regeneration. When that anxiety becomes explicit in “Apple Lover,” Hawkes’s control takes on a stark splendor and urgency. A fluid syntactical architecture brings us from butterflies drinking from a “fallen Bramley” to the pointedness of “I dreamed I could feast too / because it’s been years / since it happened, and I don’t talk about it much.” The transformation in register is total yet necessary, natural as a change in tides, natural as an earthquake’s sharp interruptive significance, painful because pain and the active engagement with pain are the substance of these two poems’ internal music. The structural trajectory of “Apple Lover,” from sumptuous idyll to a recollection of sexual assault and its aftermath, speaks most fluently to Hawkes’s achievement when, in the poem’s subsequent return to the pastoral ecstasies of its opening, the language enacts a complex liberation for and by and through the speaker—we return to a nature poem, but with richer accents and deeper perception than at the start, because with a renewed understanding of natural significance—a growth of selfhood that at once includes beauty and reckons with sorrow. “Apple Lover” becomes the luminous, gushing song of “all of me poured into yes,” a gorgeous Whitmanian affirmation of selfhood. This procedure takes on sharper edges in “Some Boys Terrify Marine Creature (6),” whose idiosyncratic extended metaphor begins uses a crossword puzzle clue (as explained by an author’s note) for a tremulous essay on cruelty and resilience. Just as “Apple Lover” never resorted to merely “motivational” rhetoric, “Some Boys Terrify Marine Creature (6)” is wholly free of triteness—its injunction to “neatly behead / the boys, cut the terror in two” is a wonderfully refreshing alternative to easy platitudes about forgiving and forgetting, sharpened by the dialectic energy Hawkes summons here, the vivid contrasts between the cruel “boys” who have “made a circle” around and “are laughing” at the target of their viciousness—a scene painfully familiar to so many of us– and the “marine creature” who rather thrillingly wins the day. The analogy is straightforward but versatile, incorporating the ineffectual “ocean,” whose “quiet song, not loud enough / to drown the high flayed pain that tastes like salt” stands with bitter accuracy for all bystanders to the world’s ugliness—and, with masterly strokes of pathos and perspective, incorporating also a second-person narrator whose interpretive drive elevates the bare fact of the marine creature’s struggle into a living symbol, an account of just how and why “there are always / routes out, / always more meanings than you think.” Brooke Kolcow reads an excerpt from "Eat Your Heart Out", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue5/17/2021 by Becki Hawkes. There is so much to relish in Carson Sandell’s work: these are poems rooted in both the natural and the supernatural, delicately sensual, designed to suck a reader in, bind them with sharp, vivid imagery—and put them firmly on edge. I loved the opening to “Poltergeist”: the way its evocation of longing and romance—“I sense your honeysuckle heart”—turns to violence in the line that immediately follows: “is ripped like ghosts from graves”. It’s both beautiful, and deeply unsettling—as is the poem itself, which combines the direct, lover-like address of its speaker (“I, your desperate poltergeist”) and their intense desire for recognition with an effectively eerie final image (“…lips and fingers extract ectoplasm”). Even when reading in your own head, you instinctively read it in a hushed, desperate whisper. “Crystal Carapace”, too, is a poem that comes alive when read (or whispered) aloud: the alliterative loveliness of the title —a phrase you just want to say again and again—is echoed by similarly satisfying lines throughout the poem, such as: “Fast forward to fall/And I’m fully flavoured”. As with “Poltergeist”, however, it’s the horror and strangeness that ultimately stay with you, alongside the considerable beauty. The poem pulls us through the seasons, images of death and lost Paradise lurking underneath the fecundity—summer is a time to “sprout, but autumn sees apple flesh grow “Crisp enough for Adam/sweet enough for worms”. The final lines, in particular are just haunting: As I’m immersed in ice My craved contents rot My sought-after blood Blends in with pale dirt And I linger as a crystal carapace The poem made me think of the pictures of icy “ghost apples” I’ve seen online—but while the usual reaction is to these images is one of wonder and curiosity, Carson’s work reminds us that, while the natural is often heartbreakingly beautiful, it is never safe. These poems, so alluringly lovely on first read, bring us back to our own mortality, and our own irresistible desire to “linger”. Grim stuff— gorgeously done.

TEXT:

When the sun sets and paints the sky into a dulcet pink, the hue is a bit off. Just by a fraction, you think, so miniscule that you might be making too much of it. But the sky looks like it’s melting into an unnatural wax, and the cicadas—they’re loud. They’re *always* loud anywhere, but at night, you think maybe you’re just imagining it when their song sounds just a pitch higher than it should. The locals don’t say anything when you ask. They smile good naturedly, and ask if the deer are giving you any trouble. The deer do get a bit territorial this time of year, yes. Tourists have problems with them. You decide it’s better not to mention that you’ve never seen them eating grass.

TEXT:

Your hills have been burning for centuries. Rise! Open your eyes and feast your bare guts on a white sun molting to black dwarf beginning at wildfire sunsets. Rise rise rise and draw up a tub for next life’s bloodletting. You could live in a moon colony. Find out which friends were imposters all along and invent new ones. Finish scrapbooking.

TW: suicide, self-harm

TEXT:

Amy J reads an excerpt from "The Temple Yields Like a Lamb", forthcoming in Wrongdoing's first issue5/1/2021

TEXT:

God says when i encounter a lion i must fold / myself under him & i’m like ok big guy as if but i do & i leave / a lily on the tabletop so the viewer sensing / my absence in the photograph will know where to look for me. God says fold / & i say into how many halves? a fragile / leafpaste slivering itself. God says be good but i’m worsted; i’ll only walk / barefoot when you lay your palms on the ground |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed