|

TEXT:

0 Comments

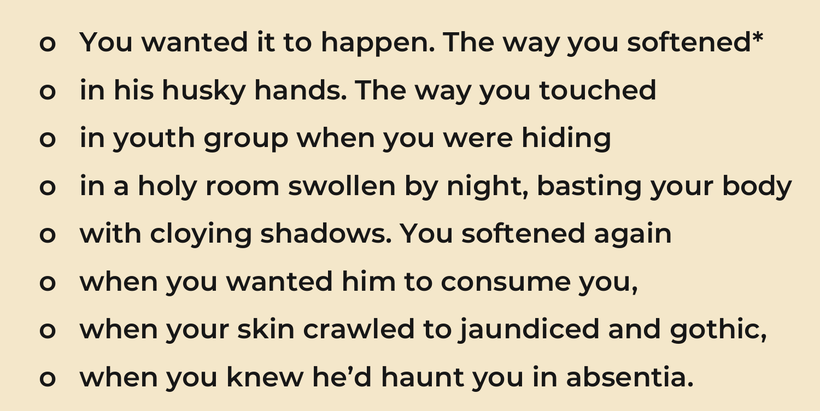

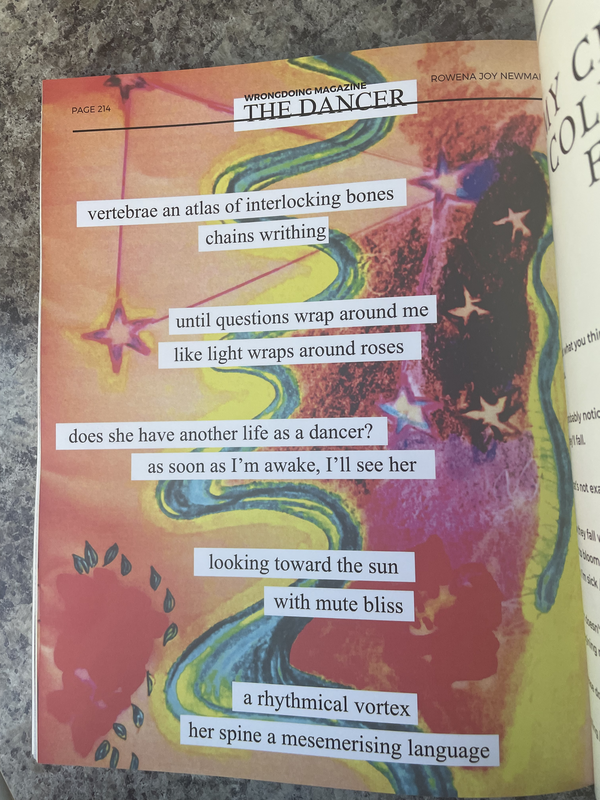

by 婕 Venus Cohen. Rowena Joy Newman (she/they) has created a beautiful, self-contained universe within short poem and visual art piece, "The Dancer". Immediately, the reader is treated to a fantastical sensory experience, resulting from the array of colors and textures settled behind the simple black and white wording. The use of a warm color gradient background provides serenity for the eye to settle on, while the cooler and more bold colors in the center of the piece show both chaos and individuality. Within the swirling vortex of colors are representational objects—stars, constellations, falling petals, and perhaps flowing dark hair to the right side of the painting. The writing is equally captivating; it's the story of a dancer… or is the story of a dream? Could it both, or neither? With only 10 lines, Newman manages to craft poetry that is both full to bursting with descriptive language for readers interested in a purely aesthetic experience, while also providing a platform for analysis and critical thinking that benefits those who like being challenged by their poetry. I am personally of both camps, and have read this short piece over and over, each time discovering new things to see, and new connections to make. The poem evokes the image of a twisting spine, a fluid body, and the visual element follows suit, with the blue-green ribbon through the center exemplifying a spine for the poem itself. After spending quite a bit of time with this work, I cannot wait to see what else Rowena Joy Newman has in store for the art and literary world. by Lorelei Bacht. (photography pictured is by Bobby Miller) “Coveting My Neighbor’s Flowers” is a short and surreal promenade in which the reader is invited to walk the fine line between beauty and fault. Mostly un-delineated and inventive in its punctuation, it is as if the lines had been subtly shifted around between the first draft and the version presented here, thus creating an openness, an ambiguity in which the reader can reside for a while—an opportunity for contemplation. As a failed gardener herself, and coveter of other people’s flowers (which may or may not be flowers), this reader can only sympathize with the all-too-human feelings of envy, despair, and attempts at communion expressed in the poem. “How I craved them immediately”. Do we ever outgrow the so-called oral phase? Is Eucharistic communion not a variation on wanting to devour our mothers’ gardens? There are psychoanalytical resonances here, shades of do-not-put-this-in-your-mouth, evocations, perhaps, of other faults. What is beauty? How do we partake in it? Is the wish to partake in it not doomed from the very beginning? The petal, the butterfly, the wafer, the body of Christ. All desired, yet unattainable: “beauty to swallow / that I feel like I stole.” The complexity of the human condition contained in this short, deceptively simple, deceptively mundane tale of a gardening “fail”. This reader would argue that it was worth spending seven dollars on those seeds (as per the poet’s own detailed account) to produce this little marvel of condensed frustration and ultimately, beauty. TEXT: In my closet I have a collection of fingers but it’s not what you think —don’t go! I’m finally ready to tell someone and I—please, thank you. ​ by Aura Martin.

In this haunting, ethereal poem we are invited to explore the dreamscape of Olivia DiVincenzo’s world of bodies, gardens, and dreams. “hearts ache. against thin walls.” Within the first line the poet captures our attention, and holds it for the entirety of the poem. The poem shares images of nature and the outside world. “fields of lavender sprout growth driven by hazy sun. yellow watercolor melts into azure” as an example. There are also views of the interior of house and self, such as “she fidgets in between my thighs and my collarbone she drags my mind to delusions worlds where deer have halos and i do not exist.” I love how Olivia easily sways between reflection of self and muses the world around her. As I step back and look at it, the poem looks like wallpaper, but instead of designs it’s peppered with words. The phrases, all in caps, leap out. “I FEAR I MIGHT DISINTEGRATE. AM I AN ANGEL?” and “REALITY ATTEMPTS TO CONFINE ME.” I find the writer’s use of spacing an interesting artistic choice. Whether you read this silently or aloud, the spaces surprise you and force you to think about what the writer is saying or not saying. The reader is challenged to consider whether the phrase speaks to the previous phrase, or the phrase after. For instance, “I DO NOT KNOW HOW TO PEEL MY SKIN BACK” is one sentence, but each phrase is read separately, independently. See how the meaning can be interpreted in different ways? The poem echoes Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” where you tear not only at the walls but question your own presence and place in the world, spiritually, mentally, and emotionally. There is a desire for safety and comfort, to grasp and hold on to loved ones or to those who you wish would love you. Olivia displays her anguish. She challenges you to confront your own. by Calia Jane Mayfield. Aura Martin is a poet based in St. Louis who focuses her work on prose poetry and centos. It is easy to tell from her previously published work that she has truly captured the craft and made centos into a staple of her work. Here in Wrongdoing, she writes a stunning cento entitled “The Quiet Dark” utilizing an amazing selection of work that embodies a sense of wanting and searching while coming to terms with self. With the selected pieces displayed above the work, which appears like a panel of writers at a conference, she crafts of the more beautiful pieces of poetry to be published this year. This is a poem that demands to be felt. “The Quiet Dark” is a poem that forced me to hold my breath until the very last line. Focused on the more sensual aspects of sexuality and wanting, she takes Franny Choi and Celeste Ng’s words and elevates them to new heights, infusing a deeper sense of searching for home among others in a way that is truly her own. While ‘cento’ may refer to patchwork, Martin’s poem feels more like a quilt handmade by a grandmother passed through the ages. Breathtaking and completely comforting. What heavies your pelvis, and: what shushes the ringing when you dip your skull below. I waded back out, still wet of him, too afraid to wring him out of my clothes in case I was wrong. I walked through the first boy like a pool of water churning with living things I almost remembered from dreams. What you call wet, I call room to breathe. The way she takes the lines from Choi and Ng, and creates such a visceral experience, is a unique quality that elevates her work form something simply good into a land of greatness that you can’t replicate. She brings forth an environment for her speaker to feel like a person that you want to listen to. This cento shows off Martin’s powerful ability to create tangible feelings and an ethereal sense of wanting. Time stopped the moment I started this poem, and it took my breath away with every line. I felt like the speaker and I became one the more time I spent reading and rereading the piece over and over. When it ends, you will feel the need to read it again and again, focusing on a new line each time. Martin takes and reshapes what it is to want to be and what it means to find yourself going from wanting the intangible and instead becoming the intangible. by Josephine Ornelas. CW: suicide, self-harm “Silence,” Ọbáfẹ́mi Thanni “The one who takes his own life will be / Punished with the same taking, again & again.” It is tempting to fall silent in the face of such a statement. The reality of suicide is already unspeakably shocking and tragic. An archaic law that declares this act yields eternal damnation leaves us further shocked, further speechless, and above all, hopeless. And yet, in “Silence,” Ọbáfẹ́mi Thanni’s speaker refuses to fall silent, or give up hope. “I am here against her sung hadith,” he writes. “I am here against my mother’s warning wish.” In four simple stanzas, the poet drapes language around seemingly unspeakable grief. The departed boy is “wrapped in quiet white” and “fed to [the earth]; he “opened a vein and poured into freedom.” Slowly we are given scattered images, phrases thread together, that gently gesture at the person who was lost. But these images do not come easily to the poet. Indeed, throughout he struggles against the urge to fall silent. The gasping spaces within each line embody the seeming futility of language, the unfillable gaps grief creates in us. Everyone who speaks in the poem—the speaker, the boy, the mother—experiences these gaps, these unclear holes that almost burst open with suffering. Still, the speaker will not fall silent. He defies the damnation given to the suicidal boy, “redeeming” the dead (if they need to be redeemed) through his poetry. The boy “deserves more than a minute minute’s silence,” and this poem ensures he receives more. A memorial, an act of mourning, one that can be revisited, spoken, heard. And indeed, the poem ends not with silence, but with an act of listening, its own kind of hope: “I hear the boy / Become wound afresh & afresh —a bright bleeding.” “My Mouth Holds a Funeral for the Loss of Words,” Ọbáfẹ́mi Thanni It occurs to me I talk too much. An odd thing to admit, perhaps, when writing a review, but it’s true. The main channels over which I communicate—twitter, text, and honestly, Instagram DMs—encourage thoughtless glib, sentences ending in haha for no particular reason. It seems I am never at a loss for words. They pour out of me on every forum, every moment of my day. And so, when I read the title of Ọbáfẹ́mi Thanni’s poem—“My Mouth Holds a Funeral for the Loss of Words”—I paused. What a lovely image: to lose words, and then mourn them. A slow and measured response to a rare phenomenon of speechlessness. The speaker of the poem has “a tongue heavy / with the taste of nothing to say. Another word fails.” The entire poem relishes in its own curious silence. Each line is clipped, often with long pauses between words. A funeral march of sorts, a tribute to the words that are not there. If I were the poet, I would have written more—but that is my mistake, an amateur mistake. The poet is wiser. Each line is so dense with meaning and grief, I almost wish I could see the poet’s face as he writes. And yet, the restraint and poise and beauty this poem delivers are uncanny. By the last line, you are confident the poem has done its work: “I listen to her grief, / till my hands fall quiet / & a new tongue grows.” by Cecilia Kennedy.

CW: blood, death What follows us, just beyond our reach? Stromberg’s piece “Dysregulation” explores this idea brilliantly. If “hope is the thing with feathers,” Stromberg’s winged creature is “the malevolent thing like a bird that hovers.” This dark presence lurks above Bellatrix’s shoulder, even as her name evokes the power of a massively bright star or a “female warrior.” The work builds suspense with memorable, haunting images and predictions: “When the time comes, it will swing its head down savagely, as if on a hinge.” The agonizing wait, which Bellatrix must endure is vivid: “Something like saliva drips from its beak onto her head.” All signs point downward, plunging into terror and inevitability. The transition from this fear to weariness is palpable, culminating in a fateful subway trip, where the other passengers’ reactions are both expected—and not expected. Who or what is to blame for what has happened? The opening stanza, perhaps, holds the answer—preparing us for the possibility that blame can be misplaced, but the effects are visible. by Lindsay Hargrave. Duncan’s verse marches through these beige pages with the solemnity of spoken incantation and chant. This is especially true of his first piece, titled “Love[sic],” which beats away at metaphor like a drum. Wrought with the pain of absent love, the repetition of grief, of the very word itself, is heavy with ceremony and power each time it is repeated. For instance, the below verse cuts to the core of the speaker’s grief from every imaginable angle: “In overgrown fields ascending I grieve you In an arrow of migrant plume I grieve you In the ginger and jasmine of rest I grieve you At an altar of unnamed saints I grieve you” The remaining pieces, “You Don’t Need to Know Much About Dogs to Tell She’s Thoroughbred” and “We Have Bathed in Nails and Been Restored,” enjoy similar themes that engage with ritual, religion and the natural world. Their language maintains a mesmerizing tone that invokes the authority of a cleric as they weave through enticing and challenging imagery, again inviting the reader into the realm of the supernatural. Each time I reread these three poems, they re-enchant me and imbue me longing for the intensity of ceremonial fire. Set yourself ablaze. Tryn Brown reads an excerpt from "A Confessional", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue7/13/2021 TEXT: It took what it wanted. The adornment, the silken White dress, the rounds of staled flesh plucked From the outside. The relic, enshrined in gold or Enamel, bones lent for salvation efforts wrapped in My own hands. Morning star, Be my derivative on earth. Tell me The calcium scattered across Your structure exploded from the Curved cage in my chest. by Erin Schallmoser. CW: sexual assault After reading Leonie Rowland’s story “The Dressmaker,” one might be left thinking of a myriad of things: the liminal spaces that especially women-identifying people are forced to occupy, the inaccurate saviors we make of ordinary men who just happen to show up at the right place and time, and the role of the victim—and is anyone ever really “playing” it, or are we pushed into it? The narrator of “The Dressmaker” isn’t asking for trouble or looking for love or trying to find her next wild adventure. Yet somehow, she gets a twisted alchemized version of all three as a result of speaking to a man who steps into the elevator she’s using, as a result of going along with this man’s plan for her, like any good, nice woman should. She’s looking for some help navigating the museum, and maybe in some way looking for some help navigating her own life, but her curiosity and overwhelm translate to the man as a victim lying in wait. A line from the first paragraph, “I was trying to make sense of it all—the artwork, the architecture, my own inadequacy,” drops the reader quickly and deeply into the narrator’s headspace. The sudden shift from universal to specific helps us understand how big the narrator’s inadequacy feels to her—it’s on par with the artwork and the architecture of the museum. We see her being primed to be a victim, not through any fault of her own, but because that is the reality we are living in, unfortunately. Our suspicions are confirmed when the man, who the narrator immediately believes, “will show me the impressionists,” enters the elevator. A man, showing up as a solution to a problem that maybe doesn’t even need to be solved, is a situation that many women will find familiar. The narrator says to the man, about the museum, “‘It’s like a labyrinth.’” It’s clear from the resulting actions that the man interprets this statement as “I’m helpless, please help me,” but what if he’s wrong? What if the narrator is just hoping to be heard, hoping for a little empathy, hoping to have her feelings in this moment validated? The man doesn’t offer any of that. He offers a solution—a solution that keeps the narrator quite literally tied to him. How is a victim made? Is a victim made, or is it just imagined? These are questions that come to mind as we continue through the story. As the man and the narrator view the museum together, it’s evident that the narrator sees herself as different from other women who have been trapped in the past, and she sees no problem accepting an additional favor from the man, stating, “I thanked him, thinking that most of the women were asleep, unaware of themselves, shining for someone else.” But I will be different, you can imagine the narrator whispering fiercely to herself. Where is that belief coming from? Is it her ego? Is that so terrible? Shouldn’t all women have the right, the ability, to believe “that won’t happen to me”? Shouldn’t that hope for a different, better future be available to everyone? I will caution a yes, and again look to the grey areas and liminal spaces that this story highlights so succinctly. The narrator believes in an alternate ending for herself up until the very end. While using the tool of the man’s control over her to tie back her hair, she “had no doubt that I would find my way,” and returning to the museum after hours, interprets the glow of the emergency exit sign as moonlight, and not a warning. Finally, she admits to something—not her guilt, for she has done nothing wrong—but there is a sense of admission when she states, “It is possible to be led in both directions: one moment you’re part of the aesthetic movement and the next you are naked in a cubicle.” From there, the story resolves in a series of thrilling and revealing sentences that offer the reader a satisfying gateway into horror—just creepy enough to send shivers down your spine, but hopefully not enough to have you losing any sleep come evening. Ultimately, it is that line, that line that begins, “It is possible to be led in both directions,” that sticks with me and continues to break my heart. The narrator says so much with that line: this wasn’t my plan, I didn’t know it would end this way, I thought I would be different, I thought he would be different. It is the women that she had been feeling sorry for earlier that day that offer her a piece of the puzzle that she is just beginning to solve, but it is also the women that contribute to her feeling of cognitive dissonance. One can see the future for her, a future where she is led to ask the worst question you could ask when something bad happens to you: Did I ask for this? The answer, of course, is a resounding no, but knowing that doesn’t serve as a cure-all. Contrary to popular belief, the truth, while helpful, won’t always set you free. “The Dressmaker” offers us more than truth. It offers us a chance to see ourselves more clearly—not just in the narrator, but in the man as well, and also the women, who at the end of the story we see are “wide awake, frenzied…covering themselves haphazardly with books and violins.” I can see parts of myself in each of those characters, and therein lies the beauty and strength of this story. by Kate Doughty. At times both surreal and delightfully comic, "And What of the Moth" reads like a bureaucratic fever dream in the best possible way. Fans of liminal spaces, backrooms, and dry humor will find themselves drawn into this piece as our narrator stands in an endless line, waiting for the answer to some questions: Where do pensions go when we die? And when can I leave this queue? We wait in line with the narrator as the world revolves around them: punks ‘de-punk,’ friends appear and vanish, birdsong grows more and more sinister. This piece captures the feeling of listlessness and disillusionment, and, finally, of transformation. After all, where there is a moth, there must be a flame—or is there? “In the queue, we had to pretend that cliché was the height of embarrassment—and moths, lights, you get it.” Tongue-in-cheek yet sensitive, bizarre yet familiar, this piece is like listening to your favorite pop song in a minor key. Equal parts strange and beautiful, "And What of the Moth" will linger in reader’s minds long after they break away from the page. TEXT: From the spaces between the scalloped edges at the top of my kitchen cabinets, I sense something changing. Something tells me to look up. I can’t quite place what that something is, but it’s one of those nagging feelings that grows into worry. Somehow, I’m forgetting something important. Sometimes, I think that if I reach up high enough, and in-between the curved edges, I’ll find a head or a face or something I’m not expecting. With each day the nagging grows, until I just tell myself to do it: to get on a stool and reach up there to the shelf, just beyond the scalloped part, and poke a finger in-between. ​ by Shyla Jones. CW: kidnapping, non-consent Lindz McLeod’s “Heavenly Bodies” beams in the strangest, best way. Paired with sublime language, McLeod explores a woman who keeps the sun—or, well, a sun—trapped in her lonely home. We meet Joanna who lives next door to a nosy couple that are too interested in their neighbor’s fresh tan and “impenetrable” full body clothing. What they don’t know is that inside Joanna’s kitchen blares her own personal, illegal sun. She straps on safety goggles. The light spills out from every inch of the doorway, a tsunami of visual force. Despite the eyewear, which is the kind physicists wear, she blinks until her eyes become more accustomed. She isn't sure what kind of damage repeated contact might be doing to her body. She's got a great tan, at any rate. Regular clothing doesn't prevent it. Maybe the sun is giving her cancer. Maybe she doesn't really care. From the start of “Heavenly Bodies,” you get the feeling that something is wrong, but you can’t quite figure out what. Kidnapping the sun should be a good thing, right? Having your own personal sun seems fun, doesn’t it? Throughout the piece, McLeod weaves dreamy, celestial words with gritty and a tough subject matter. By the end, you’ll feel as if the sun swallowed you too. by Amy J. “[H]ell is for those who dream in flight.” This is how Rogando ushers us into mythic, biblical word of “Poem In Which I Do Not Love God”: a speaker grasping to remember the passing wisdom of a you who is either a Lover who is Not God or a God who is Not Beloved, or both. You must be some kind of god, what with their command of celestial bodies, their authority to baptize, to declare themselves & our speaker lovers & have it writ. All the while, our speaker gazes up at you from a place of begrudged supplication, robbed—as so many of us raised young in the faith—of the “choice to convert.” Rogando’s You is an unlovely God: a lover who commands, who belittles our speaker as one who “cannot comprehend light” without their aid, who tells our speaker when the earth will shake & whose violence shakes it so. Yet our speaker broils with a violence of their own; laments, “i wish i shook with godhood / how i wish i tore your foundation like body to bread.” But the tools of our speaker are not teeth or scripture or spear—the tools of our speaker are flight & pretend. By the logic of Hell as a place for dreamers, to sin is to dream is to fly, & by the end of the poem, our speaker has taken wing. Our speaker gains dominion over the God who is Not Loved not by returning abuse, but by leaving. By ascending. By forgetting, until you wastes to nothing but “a word worn into froth . . . / a shapeless cloud / a petal drifting on light.” David Hanlon reads an excerpt from "On Opening Up", now available in Wrongdoing's first issue7/3/2021 TEXT: Your heart is a half-open window. Outside: rain slashing, wind-tickled trees rustle, bats rip-soar, shredding the night sky: black flashes illuminated by streetlamp glare, they dart in unpredictable directions above an overgrown garden, a washing line dotted with unused pegs. by Sunny Vuong. Both the falling and the flying weave effortlessly between the lines of Mandy Tu’s surreal and somber poetry. In a gentle eulogy, equally portrayed as an ode to love lost, Tu’s words compel her audience to consider the death of what once soared in raw, yet idyllic, stanzas. “We rest our heads. We wake up / hungry,” Tu writes, a confession to what remains of bloody nests and stained feathers. Tu’s work doesn’t shy away from pulling the reader startlingly close, and her entrancing use of language bares both matters of the body and quiet heartbreak. In “An Altar For Our Love,” Tu depicts the aftermath of a quiet and decomposing heartache with the stark image of a long dead bird and its nest. With a reverence for the scene, Tu writes: “Close by, a pile of bones, dragged / and discarded. We bow our heads in obeisance, / hold a moment of silence.” Tu’s poem encourages her audience to hold still as her words sweep us under their silent and aching undercurrent of the malformed corpses of what remains of the things that we loved, “red as funeral roses.” “Touch is tumultuous. / Too worn out / with mistakes / to get it right,” Tu states, hushed in her conclusion of “Touch.” Like a fleeting brush of skin against skin, Tu’s poem dances upon the meeting of harsh and jagged bodies against each other. With gorgeously feverish imagery, Tu writes tenderly of “girls with lips / like heliotropes” and the wearily burning contact of bodies made “of summer parts.” Mandy Tu’s immersive portrayal of touch pulls her audience into a similar trance of quiet, but slowly simmering, want. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed